Using Electrochemical-Impedance Spectroscopy to Image Failures in Hydrogen Fuel Cells

Using Electrochemical-Impedance Spectroscopy to Image Failures in Hydrogen Fuel Cells

Apr 1 2022

Introduction

Hydrogen is projected to be a $10T (that’s trillion with a “T”) market by 2050, or 13% of the global GDP,1 and hydrogen fuel cells have seen a surge in growth over the past few years as more of the world begins to look seriously at zero carbon solutions for transportation. Hydrogen-powered vehicles open up new markets around hydrolyzers/electrolyzers where the hydrogen is actually generated at a fueling station rather than trucking it long distances as we do with petrol today. At the heart of most electrolyzers that produce hydrogen, or fuel cells that use hydrogen to produce electricity, is a proton-exchange membrane (PEM), as shown in Figure 1. The PEM cell has the advantage of being able to operate at a comparatively lower temperature than, along with having a size and weight advantage to, other models. As long as hydrogen and oxygen are provided as fuel in the right amounts and conditions, this fuel cell produces electricity. The electrolyzer is made of similar components and operates basically in reverse: electricity is supplied to water, and oxygen and hydrogen are produced.

Figure 1. PEM fuel cell.2

As PEM fuel cells get used in more transport vehicles like buses, cars, and light rail vehicles, it becomes increasingly important to predict failures before they occur. The literature3,4 has shown that electrochemical-impedance spectroscopy (EIS) techniques can be applied to detect pinhole failures within the PEM, among other failure modes. This is typically done on large benchtop instruments sourcing currents in the range of 10s to 100s of amperes. However, these instruments are large systems and do not scale well to a transportable fuel cell that would permit in situ diagnostics. This article describes the challenges of making a portable EIS system work with 1 A to 100 A of stimulus currents, along with leveraging the advantages of the AD5941W5 EIS engine. This work can be applied to fuel cells, electrolyzers, batteries, and other low impedance systems.

Experiments

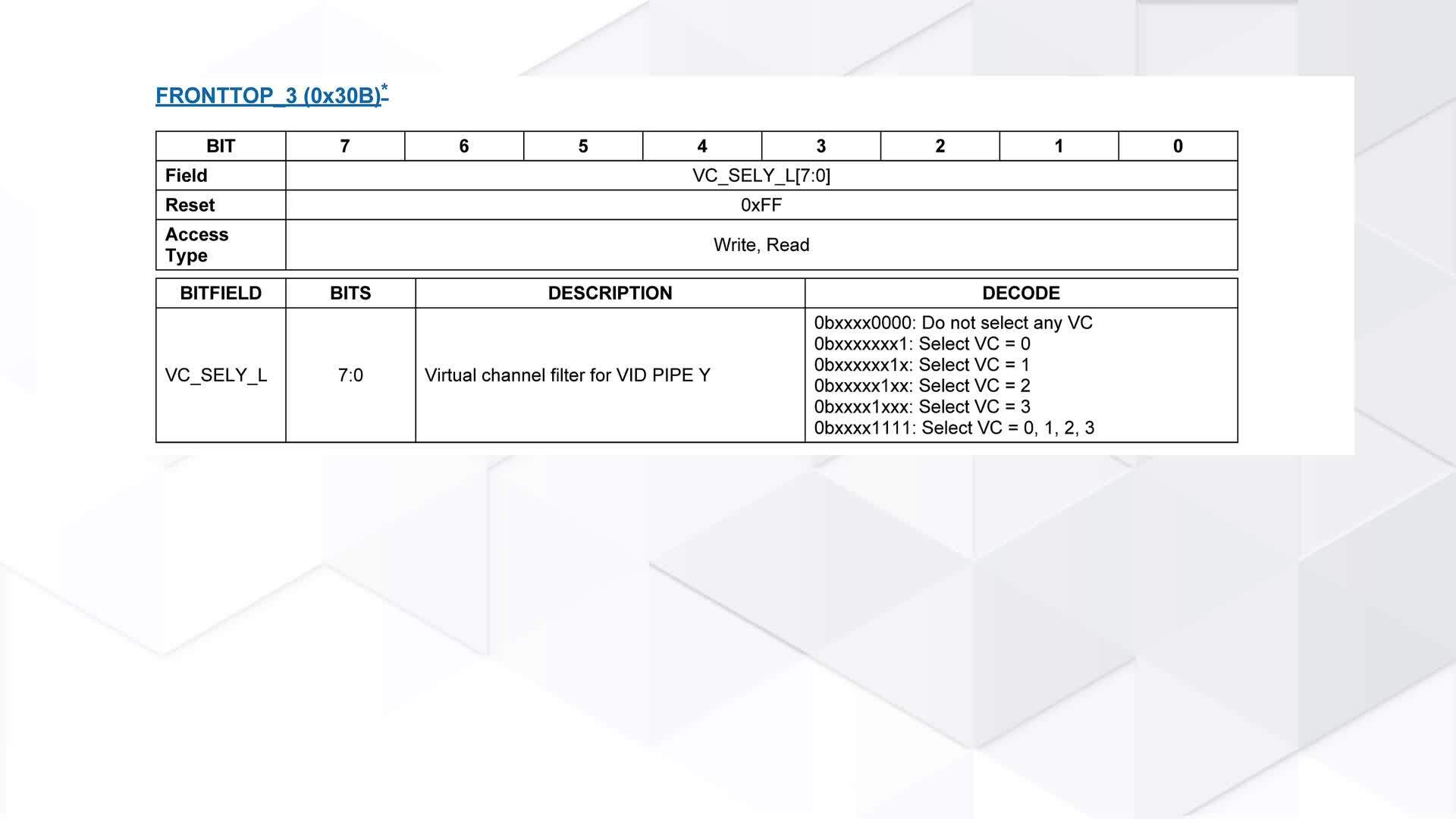

The basic measurement engine for this development is the AD5941W from Analog Devices, a high precision impedance and electrochemical front end that is capable of both potentiostatic and galvanostatic measurements. For these tests, a fuel cell (similar to a battery) requires a galvanostatic measurement where a current is generated and a voltage is measured. See the block diagram shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. An AD5941W block diagram showing the high BW AFE path for stimulus and the precision ADC path for calibration and DFT/EIS analyses.

This project began with the testing of the CN0510, a battery-specific impedance measurement board that ADI made to assist customers in impedance testing of batteries leveraging the powerful AD5941W EIS engine that allows for precise impedance measurements. Immediately, it became apparent that there were limitations in this approach, namely the low currents used for AC stimulus of the battery and the 1/f noise corner of the external amplifier used on this board, along with the use of AC decoupling for the receiver chain limiting the low frequency corner of the stimulus and receive. With expected insights in fuel cells occurring at or below ~100 Hz and up to 10s of kHz, along with stimulus currents up to 10 A (in order to get above the process noise of the fuel cell), it was clear this board would need a revision. The CN0510 is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. CN0510 battery impedance system.

One way to extend the current excitation range of this approach is to take the excitation stimulus signal (CE0 in Figure 3) and send that to a remote-controllable electronic load; in this case, the Kikusui PLZ303W.6 This approach is shown schematically in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Electrical connections of Kikusui PLZ303W to a CN0510 board.

It’s important to consider the parasitic inductance of wiring when working with 10s of amps and to use twisted wiring whenever possible to reduce voltage noise pickup. This system produced strong impedance data with standard deviations in the ~1 μΩ to 2 μΩ range on a 10 mΩ DUT, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Data from a 10 mΩ DUT using Kikusui PLZ303W.

These data were also taken across frequency to get a sense of the roll-off at the instrument from excitations, shown in Figure 6 with error bars revealing poor repeatability as the excitation frequency gets lower, owing to AC coupling in the receiver signal chain.

Figure 6. A 10 mΩ DUT measured across frequency using Kikusui PLZ303W.

It’s useful to note that the Kikusui device weighs ~10 kg, so it’s not suitable for portable electronics. However, this validates the methodology and pushes us toward miniaturization. A standard op amp-based voltage-controlled current source (VCCS) was built using the AD8618 op amp. This amplifier was selected for appropriate gain BW along with decent precision performance. This is shown schematically in Figure 7.

Figure 7. The circuit used for discrete VCCS testing.

While a complete derivation of the circuit in Figure 7 is beyond the scope of this article, it merits attention that any longer wiring should be twisted along with using local decoupling to manage for parasitic inductance. C2 in Figure 7 serves as a noise reduction cap but does contribute to frequency roll-off above ~1 kHz. Figure 8 shows the updated block diagram for the measurement circuit.

Figure 8. An updated block diagram with a new current exciter stage.

A custom Python script was developed to allow direct control of stimulus frequency, and DC and AC amplitudes on the excitation node, along with calibration resistor adjustment. The excitation signals and received signals are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Excitation and received signals at 1 Hz and 10 Hz from active current sink: Ch 1— AD5941W CE0 output, Ch 2—excitation current, Ch 3—SNS_P input signal, Ch 4—attenuated signal to op amp.

Results are shown in Figure 10 for this active current sink, along with results taken with different decoupling capacitors in the receive signal chain in Table 1, which shows the standard deviation of error in real impedance across decoupling caps.

Figure 10. Returned data from 100 mΩ real impedance (N = 10) showing errors at a lower frequency.

| Real Std | Imaginary Std | ||

| 2.2 µF | 10.17873 | 7.712895 | mΩ |

| 22 µF | 8.63443 | 6.755872 | mΩ |

| 100 µF | 3.75349 | 7.49259 | mΩ |

It’s clear that the input capacitors in the receiver signal chain are having an effect on both the mean impedance measurement but also in its repeatability. Larger capacitance values improve the standard deviation of error, and 100 μF is the largest size that would physically fit on this board.

Turning down the impedance of the DUT to 10 mΩ shows a similar error at lower frequencies and is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Returned data from 10 mΩ real impedance (N = 10).

This experiment was further extended down to 1 mΩ in order to assess how much error creeps into the measurements. This is shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Returned data from 1 mΩ real impedance (N = 10).

Now that the basic electronics capabilities have been proven out using resistors, the next step is to apply these methods to an actual fuel cell.

Fuel Cell EIS Measurements

Taking the circuit described in Figure 7, the next step is to look at an actual hydrogen fuel cell. A Flex-Stak7 fuel cell was tested to examine the Nyquist plot, which is a way of visualizing real/imaginary impedance where the frequencies are changed throughout the measurements. This first test is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13. A Flex-Stak fuel cell EIS Nyquist plot.

While the impedance of this fuel cell is only in the 100s of mΩ, the AD5941W, along with the active current sink, was able to image the impedance of the fuel cell from 1 Hz to 5 kHz. The Nyquist plot in Figure 13 roughly approximates what was expected from this fuel cell, and the DC excitation was larger than the fuel cell’s rated capability, as well as the experiment may have suffered from some degree of fuel starvation. The AC perturbation introduced to make the EIS measurement was also quite large and outside of the linear response for the DC excitation of the measurement. No functional insight should be read into this specific test other than showing the capability of the AD5941W EIS circuit. More testing would be required to glean insight into the response of this specific fuel cell. However, this circuit topology, when applied correctly, gives us the confidence to potentially detect hydrogen crossover, oxygen concentration, along with other potential failure modes as well.

After testing on a small hydrogen fuel cell, this methodology was then tested on a production (66-cell) air-cooled Ballard fuel cell stack to assess its viability for in situ diagnostics. This will allow operators of hydrogen fuel cells to better understand the complete fuel cell stack and its electrochemical functioning in operation. Presently, the only diagnostic available to an operator is the produced power from the cell stack. This new analytical technique could be an analogy to plugging your car in at a mechanic’s shop and pulling the error codes.

A similar setup to Figure 7 was also used to generate the applied current perturbation for the impedance measurement at a small fraction (~5%) of the intended DC operating point of the fuel cell stack. This is crucial as this allows the electrochemical system to be imaged in the linear range of operation and will then permit extrapolation of the impedance data to be applicable to the total system.8

The results of comparison testing from using a Kikusui EIS system and the AD5941W system are shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Comparison of a Kikusui EIS and an ADI AD5941W EIS system on a Ballard Hydrogen Fuel Cell Stack.

Figure 14 shows the resulting Nyquist plots when the DC operating currents range from 10 A to 60 A. The EIS measurement range was from 1 Hz (right-side half circle) to 5 kHz (left-side). The solid lines (AD5941W instrumentation) and the dotted lines (Kikusui) line up well up to the higher frequency levels where the designed limits (trade-off between stability and high frequency capability) of the discrete VCCS are beginning to be apparent. There is value in the electrochemistry at both low and high frequency EIS scans, so the best electronics to use might be use-case dependent. However, this scan shows that a much smaller handheld instrument at 1/100th the weight and size of a bench-top instrument is feasible for hydrogen fuel-cell stack spectroscopy.

It is this type of innovation in on-board fuel cell diagnostics that should assist in permitting the hydrogen economy to potentially scale up to its predicted trilliondollar market size. Collaboratively combining the best knowledge in electronics and in electrochemistry and systems design is one possible way that a fully green economy based on hydrogen fuel may begin to emerge.

About the Authors

Paul Perrault is a senior staff field applications engineer based in Calgary, Canada. His experience over the past 20 years at Analog Devices varies from designing 100+ amp power supplies for CPUs to designing nA-level sen...

Micheál Lambe joined Analog Devices in 2016 after graduating from the University of Limerick, Ireland, with B.Eng. in electronic and computer engineering. He began his ADI career as a product applications engineer before m...

Sasha Dass joined ADI in 2008 as a product engineer for the MEMS microphone. In 2012, she transitioned into a program management role in the Automotive Group before joining the Optical Sensors Team in 2015. She recently jo...

Greg Afonso is an integrated engineer at Ballard Power Systems with a diverse range of interests and skills from electronics and embedded systems design to materials synthesis and characterization to mechanical design and ...

Related to this Article

Products

RECOMMENDED FOR NEW DESIGNS

Precision Analog Microcontroller with Chemical Sensor Interface

PRODUCTION

1 MSPS, 12-Bit Impedance Converter, Network Analyzer

RECOMMENDED FOR NEW DESIGNS

Precision Analog Microcontroller with Chemical Sensor Interface