When Every Day is Experiment Day

How RPI's studio classroom model morphed into a new way of teaching that's lecture-free and a lot more fun.

I don't do lectures anymore. Not in the usual sense. And I've never had so much fun teaching.

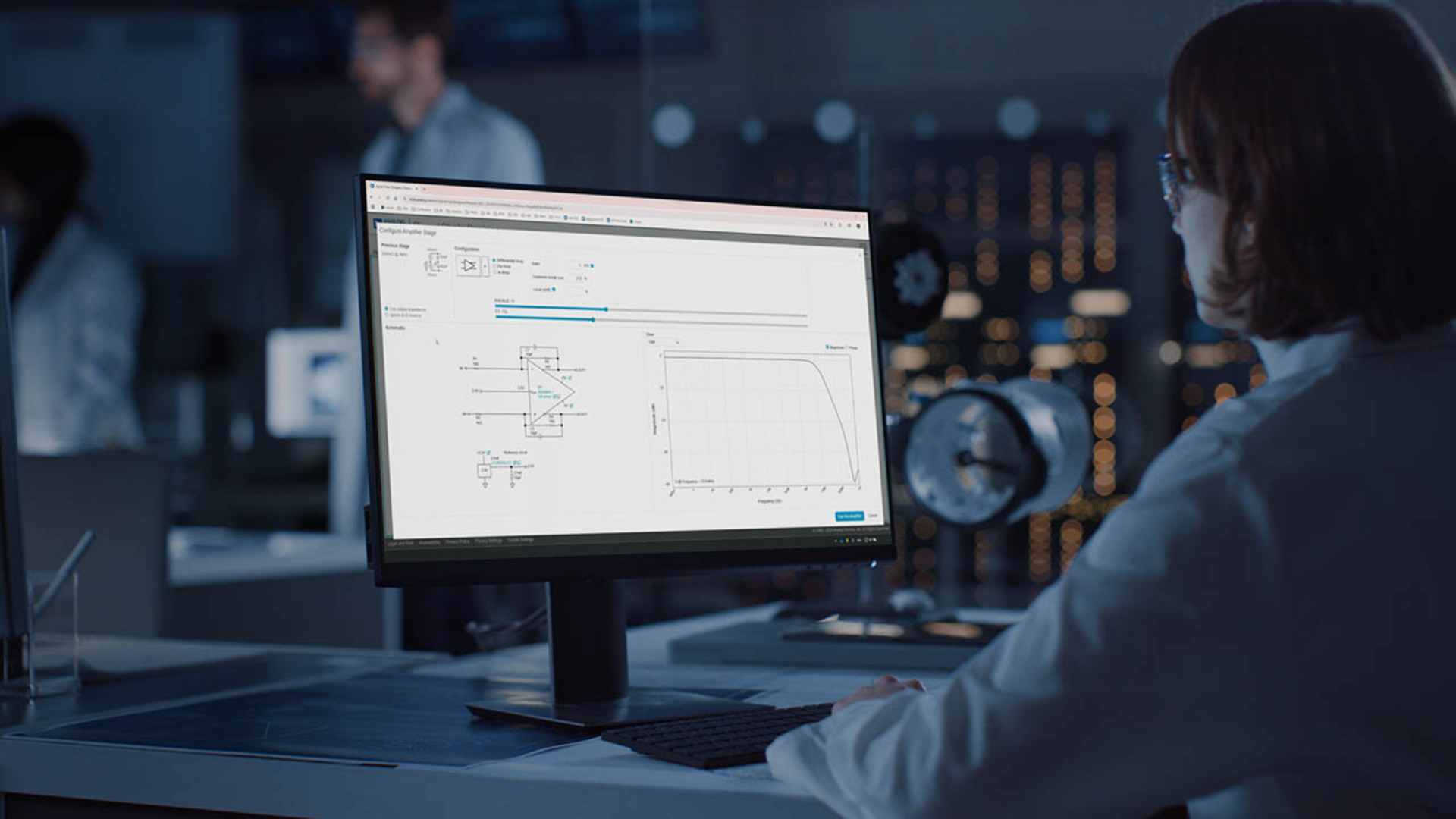

If I get an idea at home for my electronics instrumentation class, I plug in my Mobile Studio I/O Board to my laptop and build a circuit activity, record a lecture, add a paper and pencil exercise and/or a PSpice simulation, and I'm all done. I don't have to wait until I get to school and find an open time in my lab. I can even ask a TA or a former student or a colleague at another university for feedback. The students can carry out their experiments anywhere, I can do my work anywhere, and I can get help from anyone because we all have the same set of simple, mobile learning tools.

Students get the same lectures I would give in person, but the focus is doing things with the information rather than sitting passively and watching someone else demonstrate. When we meet for a two-hour session, they've already listened to the lecture, sketched out a circuit diagram, done some calculations. They're ready to build and test a circuit at their desks or may have done part of the activity at home. The recorded lectures become one more tool for the students to consult to help them through the experiments. One of my friends who teaches at a university in Utah won't let students into her electromagnetic theory class unless they prove they've watched the lecture; they have to bring what many of us now call a "ticket" that shows they've done the reading and some kind of homework. The whole point is to use the class time well.

When students complete a lab experiment at home or in a staffed lab on campus, they come to class more ready to explain what they've done, why they think the approach is correct, and with explanations for or questions about any problems they have encountered. What is so cool is that the student learning experience has all the key aspects of the complete engineering design cycle no matter where they do the work. The combination of traditional paper and pencil calculations, simulation and experimentation leading to a practical system model makes it possible for them to think and act much more like practicing engineers.

Here at RPI, we call this hands-on approach to teaching the Mobile Studio Project (mobilestudioproject.com). The concept morphed from earlier work at RPI in studio classrooms for which the ECSE department received the 2001 ECE Department Heads Association Innovative Program Award. Rather than having separate lectures, problem sessions, recitations, computer labs and traditional experimental labs, studio courses incorporate all activities in the same facility. This permits the introduction of hands-on experiences in every class. In the old (pre-2000) days, there was a huge disconnect in how we taught engineering. Lab was often scheduled for a different semester from the lecture class or maybe you didn't get the lab class until you were a senior. This was definitely nothing like the real world where you try an experiment first and then read more about it.

So in the late '90s, RPI built some fantastic but hideously expensive facilities - about $10,000 per seat - called studio classrooms to bring multiple engineering activities into one well-outfitted room. Each station had a full set of lab equipment, a desktop computer and tables for taking lecture notes and doing hand calculations. There was a natural progression from introducing a topic and advancing to paper and pencil, simulation, and experiments with breaks for group and on-on-one discussions Maybe there was an hour of lecture or maybe ten minutes but after that the class would try something. More often than not, the class began with a demo or a hands-on activity. You build, you talk.

It was so much fun. I just loved it. We thought we'd ushered in a new way of teaching. But very few engineering schools adopted this model because it was so expensive and the classrooms did not allow for easily adding students to a section because they mostly hold just 30 to 40 people. Our enrollments went up and we had more students than we knew what to do with. The model didn't scale, even for us.

With the advent of laptops, we realized we didn't need a special studio room. We could do all of the activities except for those requiring access to lab equipment. We just had to figure out a way to add that capability to the student laptop. We tried a variety of existing options, mostly involving some kind of inexpensive data acquisition board but either they did not have the functionality we needed or they were much too expensive. Students and faculty will just not adopt anything widely that costs more than a typical textbook. And then we discovered we were at one of those magical crossroads where it became possible to imagine that every engineering student could be given their own personal mobile electronics laboratory. What happened? On a global scale, the relentless quest of the electronics industry for new products that perform better and cost less gave us the basic set of building blocks we needed. Add to that the exceptional talents and vision of Don Millard, who led the Mobile Studio project at the time and is now at NSF leading new efforts to transform undergraduate education, the creativity of his student Jason Coutermarsh (now working at Analog Devices), the remarkable support of industry leader Analog Devices Inc. and Analog Devices Fellow Doug Mercer (RPI '77), and multi-year funding from NSF for a development team from RPI, Howard and Rose-Hulman, a unique university-industry-government partnership produced and fully classroom tested the Mobile Studio and the exciting new pedagogy it makes possible. Our Mobile Studio Project kit includes hardware/software providing lab-like functionality (scope, function generator, power supplies, DMM, etc.) typically associated with an instrumented studio classroom. The latest version of the hardware, now supplied by Analog Devices, costs about $150 per student. Cheap enough to ensure every engineering student gets their own board. They really grumble when they have to share.

So now we can take a studio approach in any decent classroom. Most importantly, we have been able to demonstrate increased levels of progress when students use the Mobile Studio through extensive assessment provided by the University at Albany's Evaluation Consortium Exam and homework scores go up. Students can pursue their own ideas, build something and then try it either just for their own satisfaction or, in my class, for more points. Even students who are normally not so great at analysis can work through the process and produce something like a working filter. This is a way of teaching that is much closer to the way engineers do their jobs and allows the students to build understanding starting from what they do best rather than the limited number of options we used to have in a traditional classroom.

Once students could do labs at home, all of a sudden it opened up dimensions we hadn't thought of before. Courses that never had lab experiments have them now. For example, mechanical and civil engineering majors enrolled in intro to circuits courses at Rose-Hulman learn circuits through mini labs lasting maybe 20 minutes long. Student can now be asked to do hardware homework. They can also tinker away on their own projects.

As I said, if I get an idea at home, I just set up my Mobile Studio, build the circuit and see what happens. I don't have to wait for the classroom. This is the direction engineering education is going. New modes of delivery made possible by an ever increasing array of products like the Mobile Studio I/O Board will make the present way we teach unrecognizable. I might never need to stand behind a podium again.

And I'm glad.