Sensor Fusion Approach to Precision Location and Tracking for First Responders

Sensor Fusion Approach to Precision Location and Tracking for First Responders

by

Bob Scannell

Jul 1 2016

The precision location of first responders deep within GPS denied infrastructure has been an elusive goal of the fire safety and emergency personnel community for well over a decade. The objective is to pinpoint location to within a few meters, over the course of tens of minutes. These coincidentally are nearly the same goals as found in guidance systems on tactical missiles, for which the solutions of choice today can cost $10,000 minimum, and have prohibitive size, weight, and power. Those same solutions were used in early proof of concept demonstrators for first responders, but were proven to be barriers (cost and size) to actual deployment.

First responder location determination, therefore, remains one of the most complex location applications in existence today. There is no one silver bullet sensor that can achieve the desired goals but multiple technology nodes are necessary, each of which are at the leading edge of capability. Furthermore, it involves a large scale sensor fusion and system integration approach.

Cost-effective, high performance MEMS inertial sensors can now provide the seed for a potential solution. This article envisions a complete sensor-to-cloud sensor-fused system including highly sophisticated algorithms.

The major approaches and enabling technologies are described below in Table 1.

| Goal | Approach |

| Infrastructureless Means to Detect Movement/Position | Inertial sensors |

| Ability to Precisely Determine an Absolute Reference Point | UWB radio ranging |

| Sensor Processing to Optimally Merge All Signals of Opportunity | Kalman and particle filtering algorithms |

| Robust Communications Links |

Body and backhaul reliable comms |

| Maps, Search/Rescue Coordination |

Cloud-based analytics and data basing |

The major challenges presented to the system developer can be summarized into the following three broad categories: procedural, environmental, and sensor fusion. The highly complex nature of the first responder mission, coupled with the challenges posed by the varied and extreme environment, must be comprehended without compromise in the course of designing a multisensor solution.

Procedural

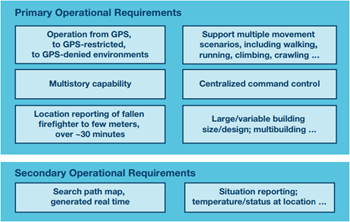

The fire safety search and rescue mission follows a highly disciplined process, which at the same time must adapt to fully nondeterministic real life scenarios. A deployable precision location system must adapt to existing processes and equipment, to the greatest extent possible. One requirement resulting from this is to be operational without any fixed or ad-hoc infrastructure because first responders are typically burdened with significant equipment (weight and cost) already. Any system development should be guided from the early stages by the goals of achieving miniaturized embedded equipment and per responder costs on the order of a smartphone. It is useful to point out here that existing smartphone location performance is highly inadequate, thus the challenge. Figure 1 outlines the most relevant primary and secondary operational requirements of the desired system.

Figure 1. Key operational requirements defining the first responder design problem.

Environmental

While outdoor positioning has become ubiquitous with GPS coverage, a fully indoor or mixed (indoor/challenged outdoor) environment is far less supported. Some indoor positioning situations (such as a shopping mall) can be realized with installed infrastructure—however, these are neither precision, nor practical for the first responder goal. For the system designer of a tracking system, the following considerations drive design definition, component choices, and risk mitigation approaches:

- RF propagation paths.

- Temperature/shock effects on sensors.

- Potential for damaged/altered infrastructure.

Sensor Fusion

The challenges previously noted in process and environment are the basis for the central design approach for this problem, sensor fusion. Relevant primary sensing modes are selected to provide uncompromised performance in critical operational modes, while at the same time complimentary sensors are matched to the key obstacles for each phase of the application, as illustrated in Table 2.

| Sensor | Benefit | Limitation | ||

| Absolute Reference | Dynamic Response | Infrastructure Free | ||

| External GPS/RF | • | No Line-of-Sight Access | ||

| Inertial MEMS | • | • | Drift Error | |

| Magnetic | • | • | Field Interference | |

| Barometric | • | • | Environmental Sensitivity | |

Because of MEMS ability to operate free of external infrastructure and to provide precision in a dynamic environment, it is expected to play a primary role in the overall solution—if capable of operation in extreme environments and if coupled with the appropriate secondary sensors.

Progress in MEMS

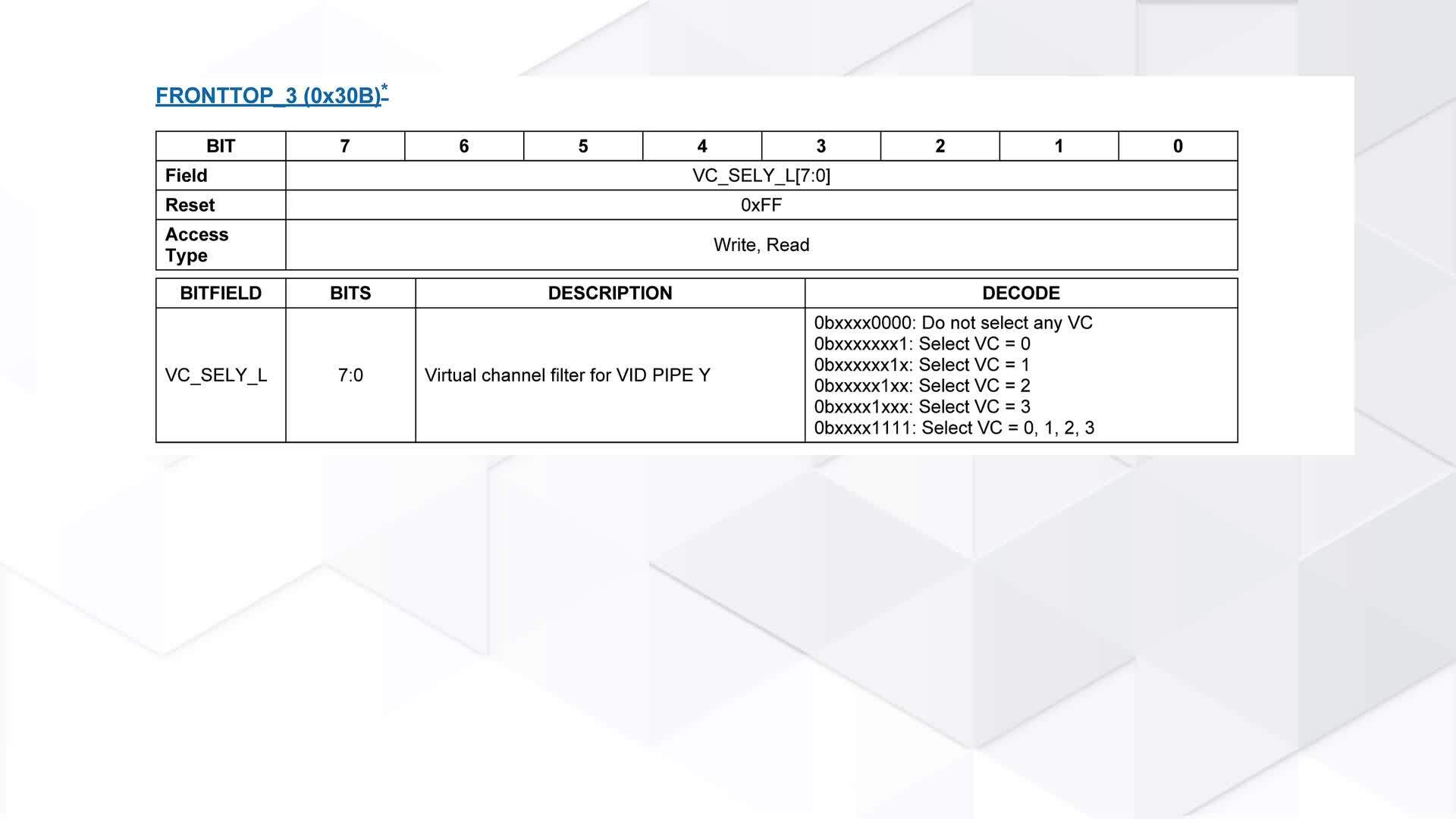

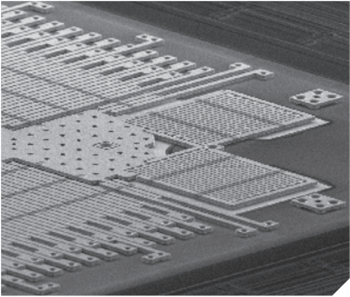

While consumer inertial MEMS devices have raced toward commoditization (with limited focus on performance specifications) and military MEMS have remained prohibitively expensive, industrial and automotive MEMS (see Figure 2) have aimed toward an enabling level of both performance and cost.

Figure 2. Industrial targeted MEMS devices are capable of low noise and stable operation, even under extreme motion dynamics.

The industrial and automotive sectors require accurate sensing in relatively complex and extreme environments, compared to the consumer sector, and suppliers to this sector have incorporated architectural features that are specifically tuned to reject performance detractors such as off-axis motion, vibration, and shock events, and errors that are induced due to time and temperature. While such design features are often most easily accommodated via larger sensors or more costly processes, the economic pressures of both automotive and an increasingly important industrial market, force a more critical approach to designing for both performance and cost-effectiveness. The result is a highly attractive performance/price positioning for MEMS components, which are specifically developed for industrial applications, as shown in Table 3, where the percentage of error relative to distance traveled is compared for three major classes of components. Industrial grade MEMS can provide nearly as good navigation capability as high end military devices, while at a reasonable price delta to the commoditized consumer MEMS components.

| MEMS Performance | Error, as % of Distance Traveled |

| Mil-Grade | ~0.1 |

| Industrial | ~0.5 |

| Consumer | >>25 |

The reason for this advantage requires a deeper look at the critical specifications of a MEMS component relative to the targeted application. In the case of the first responder goal, one critical task of the MEMS sensors is to discern the type of movement being experienced, and measure the steps and stride. As opposed to a pedestrian motion model, the first responder movement will be more random, dynamic, and difficult to discern. Furthermore, because of the accuracy goals, the sensor must be able to reject false motion such as vibration, shock, and side-to-side rock/sway of the foot or body. Rather than a simple accuracy analysis based around the noise of the sensor, which may be sufficient for a pedestrian model, the first responder model must also include key specifications such as linear-g rejection, and cross axis sensitivity. Table 4 provides a side-by-side comparison of an Industrial and low end MEMS device, looking at the RSS error combination of three notable specifications. It can be readily seen that noise is not the detrimental factor, but rather the linear-g and cross axis performance, which many low end devices do not even specify, are the overriding concerns.

| MEMS Specification | Industrial | Low End | ||

| Performance | Spec | Impact | Spec | Impact |

| Noise Density (°/sec/√Hz) | 0.004 |

0.036 | 0.0100 | 0.089 |

| Linear-g (°/sec/g) | 0.01 | 0.020 | 0.100 | 0.200 |

| Cross-axis (%) |

0.09 | 0.090 | 2.00 | 2.000 |

| Projected Error (°/sec) | 0.099 | 2.012 | ||

| Assumptions: 50 Hz BW, 2 g rms vibration, 100°/sec off-axis rotation | ||||

Though only a short number of years ago, high performance inertial sensors were primarily only achieved from approaches such as fiber optics, industrial MEMS processes have now clearly proved they are up to the task, with a relative comparison of key navigational metrics noted in Table 5 below.

| Error | Industrial MEMS (°) | Fiber Optic (°) |

| Heading | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Roll | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Pitch | 0.10 | 0.08 |

An industrial MEMS IMU example is the ADIS16488A, as illustrated in Figure 2, which incorporates ten degree of freedom high performance sensing, and has also been qualified for among the most demanding of applications, commercial avionics (as indicated in Table 6), demonstrating its readiness for the extreme application demands of first responders.

| Inertial Sensor, Stability | 5°/hr, 32 micro-g |

| Bandwidth | 330 Hz |

| Linear-g Effect, Vibration Rectification | 9 mdps/g; 0.1 mdps/g2 |

| Tempco (Bias, Sensitivity) | 2.5 mdps/°C; 35 ppm/°C |

| Temp/Vibration/Shock | DO-160G, Mil-Std-810G |

| Reliability | >35,000 hours |

| Design Assurance | DO178/254 |

Advances in inertial MEMS performance, with continued proof of quality and ruggedness, are now being combined with significant strides in Integration. This last hurdle is particularly challenging, as sensor size can be inversely proportional to both performance and ruggedness, if not carefully managed otherwise. A highly strategic, coordinated, and challenging series of process advances must be proven and merged to enable the level of performance density required of this application, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Industrial MEMS IMUs are advancing in performance, size, cost, and integration (no compromise) to uniquely enable critical applications such as first responders.

Sensor Weighting

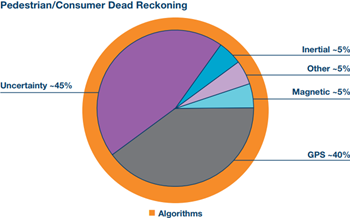

The selection of appropriate sensors for a given application is followed by deep analysis to understand their weighting (relevance) during different phases of the overall mission. In the case of pedestrian dead reckoning, the solution is dictated primarily by available equipment (such as embedded sensors in a smartphone) rather than by designing for performance. As such, there is a heavy reliance on GPS, with the other available sensors such as embedded inertial and magnetic, offering only a small percentage contribution to the task of determining useful position information. This works reasonably well outside, but in a challenged urban environment or indoors, GPS is not available, and the quality of the other available sensors is poor, leaving a large gap, or in other words, uncertainty, in the quality of the position information. Though advanced filters and algorithms are typically employed to merge these sensors, without either additional sensors or better quality sensors, the software does little to actually close the uncertainty gap, which ultimately significantly lowers the confidence in the reported position. This is conceptually illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Smartphone-based pedestrian navigation relies primarily on GPS, with supplemental but not optimized pre-embedded sensors, leaving a significant gap in high confidence or reliable coverage of motion detection, which algorithms alone cannot fix.

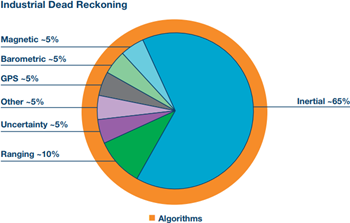

By contrast, the industrial dead reckoning scenario, such as first responder, is designed for performance with system definition and component selection guided by specific accuracy requirements. Significantly better quality inertial sensors allow them to take the primary role, with other sensors carefully leveraged to reduce the uncertainty gap. Algorithms are conceptually more focused on optimal weighting, hand-off, and cross correlation between the sensors along with an awareness of environment and real-time motion dynamics, than they are on extrapolating/estimating position between reliable sensor readings (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. With sensor selection specifically targeted at full coverage of the first responder mission, the accuracy and reliability of the system is greatly enhanced.

Accuracy in either case above can be improved via improved quality sensors, and while the sensor filtering and algorithms are a critical part of the solution, they do not by themselves eliminate the gap in coverage from limited quality sensors.

Precision Location and Mapping (PLM) System

For the specific case of first responder tracking, the mission has been partitioned into the following stages, in order to best assess sensor processing requirements: arrival at scene, deployment, inside the building, and rescue—Table 7. It is envisioned that the fire truck is equipped with a high end GPS/INS system, which is capable of geofixing the position of the vehicle upon arrival at the scene, as a known reference point. From this point, and until the firefighter enters the building, there is an indeterminate and random sequence of movement for which the precision location and mapping system relies on an ultrawide band ranging implementation to maintain an accurate fix of the firefighter position and orientation. Upon entry into the structure, the inertial sensors become the primary tracking sensor with the goal of providing location accuracy of a few meters. The system is designed to solely rely on inertial sensors if need be but also be able to take advantage of other signals of opportunity when available and reliable, such as UWB ranging signals, magnetometer corrections, and barometric pressure measurements. As discussed earlier, the implemented algorithms not only track location, but generate a real-time path map of the search pattern. If a firefighter goes down or is in distress, the map generated from the initial path is a supplemental sensor input to the rescue firefighter who is also guided by inertial sensing.

| Mission Interval | Primary Sensing | Auxiliary Sensing | Period | Accuracy |

| Arrival at Scene | GPS | Inertial | — | Map Fix |

| Deployment | UWB | Inertial | Unknown | Decimeters |

| Inside Building | Inertial | Signals of opportunity | ~30 minutes | Meters |

| Rescue | Inertial | Path-map, other | Minutes |

While high performance sensors are certainly at the heart of the PLM system, the following are critical enablers of the system as well:

- Deep understanding of the component sensors, and their drift characteristics/limitations under stress.

- Extensive knowledge of the human body movement model.

- Detailed application level insights and operational modes definition.

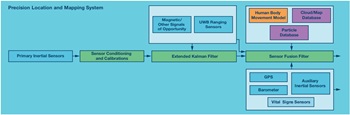

These provide the definition, guidance, and boundaries for the implementation of the sensor fusion processing (see Figure 6). The core of the processing is a particle filter, which tracks multiple possible movements over time, eliminating errant paths as the filter distinguishes them. The sensors themselves are distributed on the firefighter for optimal performance and a wireless body network, as well as a rugged back haul communications network seamlessly connect firefighter, rescuer, command and control, and cloud-based maps and coordination where possible and useful.

Figure 6. The PLM system is a complete sensor fused solution based on high performance sensors, complementary sensor filtering and processing, and cloud-based databases and analysis. The outputs are precise location and a search path map.

The precision location and mapping system provides an infrastructure-free approach to detecting position, leveraging high performance sensors and advanced algorithms to optimally merge all signals of opportunity. The system goals are meter level accuracy and real-time path map generation. Advances in industrial grade MEMS inertial sensors have enabled PLM and a full systems development approach allows addressing technical hurdles while also achieving commercial metrics.

Continuing work is focused on integrating the latest generation sensor advancements and matching these to new insights in the first responder operational scenario definition. Final integration will include optimized form factors and body placement, as well as more complete implementation of the required communications links and final system qualifications.

About the Authors

Bob Scannell is a business development manager for ADI's MEMS inertial sensor products. He has been with ADI for >20 years in various technical marketing and business development functions ranging from sensors to DSP to wi...

Related to this Article

Products

PRODUCTION

Tactical Grade, Ten Degrees of Freedom Inertial Sensor

RECOMMENDED FOR NEW DESIGNS

Seven Degrees of Freedom Inertial Sensor